YEAR

2016

2017

DELIVERABLES & METHODS

Net-Promoter Score

Lesson Plans

140+ UX Designers

Assessment Protocols

Lab Design and Delivery

Lesson Delivery / Speaking

TEAM

10 years ago I believed teaching wasn't for me. But when I started training in martial arts I began to think differently. My Sensei would say, "If you want to get better at something, try teaching it!" This change of mind led to a change of heart and is why I decided to teach UX design.

In this post, I share 5 takeaways from being an instructor at General Assembly, where we provide and cultivate space for junior designers to grow and launch their own UX design careers.

“I think the biggest design project anyone can have, is their own life”

—Jessi Arrington

When I started teaching I was surprised to hear some of the more advanced students in UXDI class complain that their less-skilled counterparts are "slowing us down" and maybe the less skilled shouldn't be doing design.

Who is the "us" that is being slowed down, anyway? We all have something to give. In fact, on the job, UX designers are more likely the ones to include non-designers in the design process. I try and remind students that we all have something we're good at and that not everyone needs to measure up to an arbitrary UX standard.

As a UX designer and instructor, I spend time helping students prepare for their role in Tech—an exclusive industry—to become advocates of a process that values other perspectives. I would argue that it doesn't take more time to include others, it's simply a matter of choice.

UX designers must be willing to accommodate others of different skills and perspectives. In fact, to be a great UX designer one must facilitate and help non-designers participate in the design process.

“You're going to hear this a lot: It depends.”

—Ashley Karr

Over the years, it's become clear to me that UX designers must become design advocates. UX designers cannot simply show up to work and expect the design process to happen without doing some education around the office. We have to communicate and advocate the value of our work in the workplace.

Students often come to class believing that others in Tech will help them learn more on the job about the "new" field of UX. They are surprised to learn that UX (and its other names) has been around for a while, that their perceptions of UX were myopic, and that many companies still struggle with what UX design is and does.

During the first cohort I taught, my co-instructor Ashely Karr answered a question with "it depends." This encouraged me to welcome ambiguity into the classroom and to recognize and allow students to come as they may, full of misconceptions and unrealistic expectations.

Over the 10-week program, we shed light on these misconceptions and help students communicate the UX design process in more nuanced ways. It's exciting to watch new designers expand their perspectives and become advocates for user-centered design.

“Placing a box in a wireframe takes seconds. Knowing where to place that box, and why, takes years of experience.”

—Nick Finck

In martial arts class, Sensei encouraged the upper belts to teach the lower belts because you have to pay more attention to what you do and why you do it. Not only does this add a critical lens to your practice, but it also trains you to begin learning self-critical techniques required for deliberate practice.

As with any discipline, practicing the same thing over-and-over without self-assessment and expert feedback only leads to muscle memory and/or rote memorization. It won't correct poor form or help one learn deeper analysis.

Frequently, I see students attempt to skip design activities because they think nothing will change their thinking until they get into higher-fidelity work. But we cannot improve our design practice by blowing past what we think we've already mastered. As a UX design instructor, I've learned to encourage students to slow down despite their fears of "wasting time."

You can always get better at sketching. But that's not the point of deliberately practicing low fidelity design activities. You do it to get better at exploring alternative design solutions; To get better at articulating the strengths and weaknesses of alternatives based on your design target.

10 weeks isn't very long to learn the depths of user experience design, but it is a great way to learn the basics through deliberate practice and quickly master the foundations of UX.

“If they knew how to make it that intuitive, they wouldn’t have called you.”

—Robert Hoekman

At General Assembly, some of the most motivated and focused students come through the program to change careers and become UX designers. While my time is often spent guiding students away from a hyper-focus on visual design, I also spend a lot of time helping students develop the skills necessary to think critically through problems and solutions.

It's common during the first project presentations to hear statements such as "the current designs are confusing" and "the solution is a new intuitive UI." Or "the user's pain point is slow checkout" and "the business needs a fast, easy checkout process." This is what Robert Hoekman would call "useless platitudes," and something I aim to get students to go beyond.

As UX designers, we have to explain how to design an experience that is fast or easy, and we have to have some way of identifying that criteria from a user's perspective. Not only is this important to articulating one's design rationale, but it's also critical to planning and designing successful products. (Easier said than done, I know...)

Students seem to avoid being specific because it seems superfluous, and therefore a "waste of time." Becoming specific is related to the point above, on deliberate practice. Often, I will observe students skip steps yet struggle when they get into digital tools, like SketchApp. They think they are slowed down by the software!

It's amazing to see, even in something as simple as a context scenario, but when I have students go back and add more detail, to slow down enough to be specific, I can see the eyes sparkle and ideas come alive. When students get more specific, everything else starts to flow.

Yes, as UX designers we tend to make our coworkers feel like they have to slow down, and they may have to. And yet, this will have a positive effect. By helping us think critically about the problem, the solution, and the strategy behind our designs, we will be more able to know what we are doing and how we will measure our success.

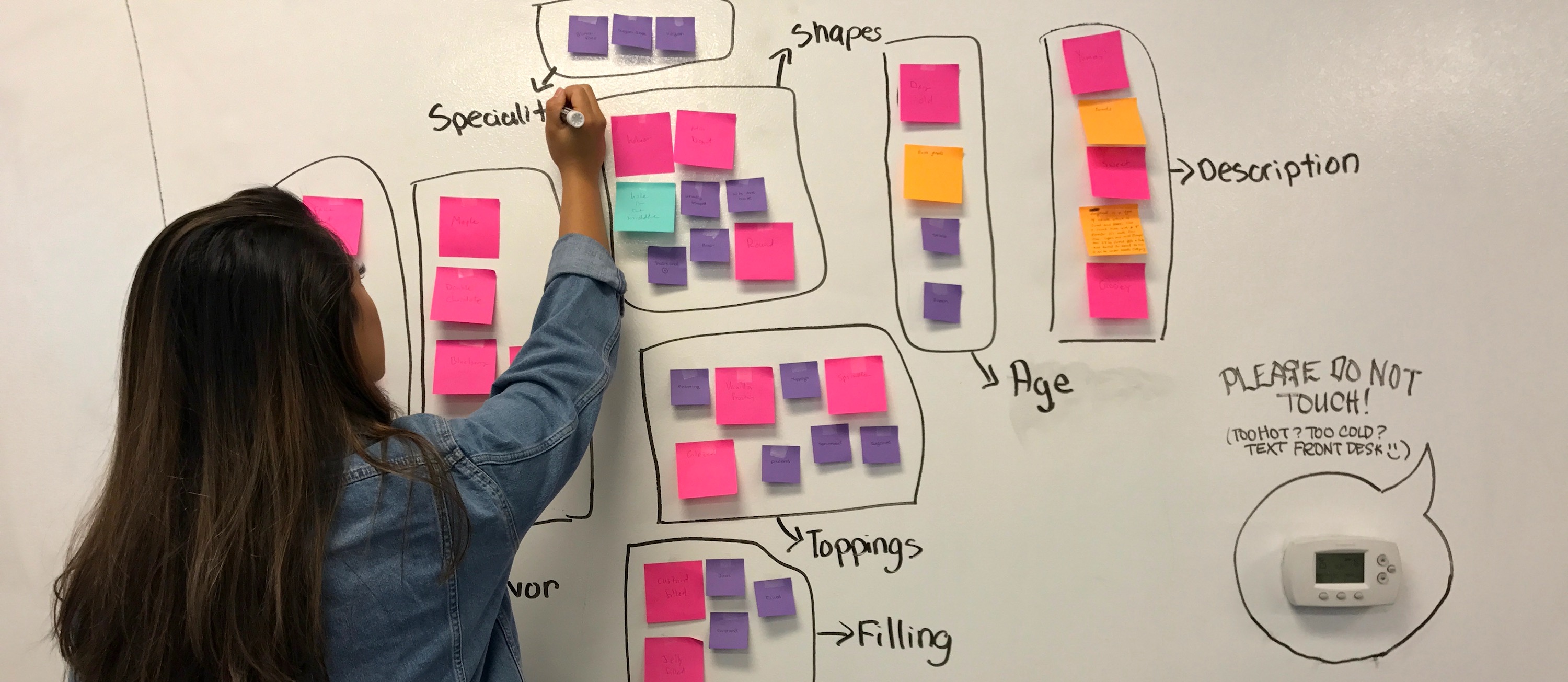

“Happy smiling people around a whiteboard means you like to collaborate. It’s not a cliche, it’s a visual language.”

—Christina Wodtke

In her post, "Your Portfolio Probably Sucks" Christina Wodtke asks designers to show examples of their work. She says "Show me what kind of work you do before the final design," and I wholeheartedly agree.

A quick Google search for "best UX portfolios" invariably sends students down a path believing they need to show shiny visuals and mockups that, to most non-designers, look impressive but to the trained eye one perceives a lack of design rationale.

Students, then, focus on creating design artifacts they say are "more complete" or "finished" or "realistic." And yet, these high-fidelity artifacts, when placed on their own, will not show one's thinking that supports the work. Where are the context scenarios, the task flows, the rough drafts of various layouts? Where is the evidence that supports the design?

The irony is that students hear they need to show their "design process" and students respond by putting a graphic of the UX design process in their case study! Wodtke says that what seems cliché, like putting a picture of post-it notes, is the way to demonstrate your UX design chops. It's the messy pictures of UX work that are iconic and what the hiring manager needs to see, not a useless graphic of the "UX Design Process."

As UX designers, we leverage clichés all the time to meet the expectations and needs of our users. Why should your UX portfolio be any different? Design tools cannot replace design thinking. Show your design activities and tell us what you learned from doing them. That's what hiring managers want when they ask to see examples of your design process.

“When students ask me 'Do I really need to do all of this?' I say, 'Do you want to get a job?'”

—Court Crawford

The design process I teach at General Assembly is necessarily rote. And by that I mean the UX design process appears too perfect and linear. I repeat "it depends" in every class and I often hear the same questions in each new cohort I teach. This artificial UX process is o.k. for someone practicing new skills, it actually makes sense.

We want students to get an overview of UX, and be job-ready. And we should expect graduates to learn on the job, they are entry-level, right? Yes, they will need additional mentoring. 10-weeks is an internship, not a magic pill.

If you're a Senior UX Designer, you should ask yourself if you're ready to grow further. Advocate within your company to hire a junior designer and discover how mentoring can help you grow in your design thinking.

I've learned to be patient and to let go of my mistaken belief that others should perform at my level in order to collaborate. Instead, my role is one of cultivating the space where students can practice, fail gracefully, and develop some improvisational skills. It's about accepting people where they are and helping them grow from that point. It takes a lot of effort and caring, and my students have helped me grow more than they know.

YEAR

2016

2017

DELIVERABLES & METHODS

Net-Promoter Score

Lesson Plans

140+ UX Designers

Assessment Protocols

Lab Design and Delivery

Lesson Delivery / Speaking